Climb Every Mountain: Scaling Mt. Everest With Diabetes

By Joe Liesman

By Joe Liesman

Taylor Adams, a mountaineer and pediatric ICU nurse with type 1 diabetes, became the first person to summit the highest mountain on all seven continents while using an insulin pump. He completed his final summit in 2020. He is climbing on behalf of the diabetes community and raising money in hopes of finding a cure.

Editor's Note: Insulin should always be taken as directed by your healthcare team. Adams, as an experienced climber and ICU nurse, understood the risks and necessities of modifying best practices due to the extreme conditions of mountaineering and altitude.

Sitting in an old minivan on a forest road in Alaska in 2011, Taylor Adams thought he had considered everything. But when the climbing guide sitting in front of him took out a photocopied journal article and asked him what he would do if his blood glucose meter stopped working above 10,000 feet, Adams was taken aback. “This was the first time I remember hearing any concern about having diabetes and climbing mountains,” he said.

Adams, now 33, had just graduated from Hamilton College and was on his way to climb Denali, the tallest mountain in North America. Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when he was 11, he didn’t see his diagnosis as something that would get in the way of his mountaineering journey at the time.

“Starting out, my parents didn’t press their concerns on me and were extremely supportive of my mountaineering,” remembers Adams.

Working in Salt Lake City, Utah, as a pediatric ICU nurse, in 2020 Adams became the first person to summit the highest peak on every continent, the so-called Seven Summits, while using an insulin pump. He originally used the Medtronic Minimed Paradigm pump system before switching to the Medtronic Minimed 670G and Guardian continuous glucose monitor. Only four other climbers with type 1 diabetes have completed all Seven Summits, and none of them completed all seven while wearing a pump.

After conquering the highest peaks in North and South America, Europe, Antarctica, and Africa, Adams decided to dedicate his remaining climbs to the diabetes community. He also turned his quest into a fundraising opportunity for JDRF to raise money for diabetes research and to show people with diabetes that their condition does not have to limit them from achieving anything. Adams posts pictures of his mountaineering expeditions on his Instagram handle @climbtocurediabetes. Photo: Adams holds a Climb to Cure Diabetes Flag on his way up Mt. Everest.

Photo: Adams holds a Climb to Cure Diabetes Flag on his way up Mt. Everest.

Diabetes and Everest

In 2017, Adams had already completed five of the seven summits, with only Mt. Everest in the Himalayas and Mt. Kosciuszko in Australia remaining. Because Mt. Kosciuszko sits at only 7,310 feet, it wouldn’t pose much of a challenge for a climber like Adams. At 29,032 feet, Everest was a different story.

“I didn’t think I could actually do Everest,” he said. “One day I was just thinking about it, and I thought that if I don't at least try, then I'll always wonder if I could actually have done it.”

Roughly 800 people attempt the six to ten week climb up Everest every year. Taking on the mountain means braving temperatures as cold as negative 40 degrees fahrenheit, winds over 100 mph, and air so thin near the summit that there is little chance of survival without an oxygen mask.

To prepare for the grueling effects of altitude, climbers approach Mt. Everest in a series of rotations going up to increasingly higher camps on the mountain and then back down. While this helps climbers get their bodies accustomed to the low oxygen environment, it also means climbing dangerous and risky sections of the mountain, like the Khumbu Icefall, multiple times. The first technical challenge of the climb, the Khumbu Icefall is a dangerous ice field full of constantly shifting walls and crevasses. Sitting atop the Khumbu Glacier, ice moves at up to four feet per day and causes crevasses to suddenly open and massive blocks of ice to crack and potentially fall.

“Having to do the scary parts several times can be really mentally challenging,'' Adams remembers. “Physically it gets easier, but some of the technical parts changed frequently in the icefall so it was always a new challenge from one day to the next.”

This process, while difficult, is what makes surviving near the summit possible. A human dropped at the summit of Everest without prior acclimatization would be dead in minutes.

This area above 26,000 feet is referred to as The Death Zone, as the air at that elevation is too thin to sustain human life for a significant period of time.

Survival in The Death Zone requires extreme fitness, preparation, and equipment. Climbers at this altitude almost all carry oxygen masks. For someone with diabetes, there are even more things to consider – including how to carry and access insulin, which becomes useless if frozen, and how to manage their diabetes devices and diet in conditions where accessing food or equipment can also be difficult or even impossible

Altitude and extreme cold can have negative effects on glucose monitors, and the conditions can cause your body to use extra glucose to stay warm, increasing your risk of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia and altitude sickness have similar symptoms but they are treated differently. Differentiating between the two conditions can make treating the problem challenging.

“If you think about your diabetes supplies, almost everything important is either liquid or electronics, and neither of them do very well at really cold temperatures,” said Adams. Photo: Adams showing his insulin vial while wearing an oxygen mask on his way to the summit of Mt. Everest.

Photo: Adams showing his insulin vial while wearing an oxygen mask on his way to the summit of Mt. Everest.

He kept his insulin warm by wearing it on a vest fit close to his chest underneath his down mountaineering suit and other additional layers. “I figured if the insulin against my chest froze, I was probably already dead anyway,” he said.

Adams always changed infusion sets while still inside a tent, as doing so while exposed to the freezing conditions in the open air could cause equipment to freeze in seconds.

“The good news,” says Taylor, “is that you are exercising a lot and not eating a lot so you would not have to do a lot of insulin changes once on the mountain.”

Beyond just keeping his insulin from freezing, Adams also needed to manage his glucose levels with the knowledge that there might be times when administering insulin or checking his glucose would be impossible.

“For the parts [of the climb] that are more exposed and dangerous, I would let my blood sugar be higher than I normally would try to keep it at home,” he said, since the risk associated with hypoglycemia outweighed the risks associated with running high.

Managing his diet at altitude was also a challenge. “Probably half of my pockets were full of all these different high sugar snacks to eat in accessible locations.”

Despite these challenges, Adams remembers a clear advantage that he had because of his diabetes. One of the main symptoms of altitude sickness is appetite loss and nausea. It’s not uncommon for climbers nearing the top of Everest to struggle with eating and even have to turn back because of it.

“To get around this, I would give myself insulin a little bit early before I ate a meal to try to get my blood sugar a little bit low.” The hunger that can come with going low allowed him to eat food despite the effects of altitude sickness.

While many of the days on Everest allowed for frequent breaks to check his glucose or administer insulin, conditions at the top of the mountain meant that stopping or unzipping clothing for any reason could be life threatening. “My insulin definitely wasn’t accessible on summit day,” he remembers.

To get ready for the final push, Adams had two insulin pumps hooked up and ready to go, with one pump on the “suspend” setting, allowing him to start it at any time in case his primary pump failed. He also carried an insulin pen in his pocket.

“I probably wouldn’t have been able to hear if something went wrong with one of the pumps [due to howling wind, snow, and extensive headwear], but it made me feel confident to keep going,” he said.

Reaching The Summit of Mount Everest

Before reaching the summit, climbers first have to pass through the Hillary Step – a steep and dangerous challenge right before the top. Climbers ascend a one way fixed line up the Step, making their way up a path between cliffs that drop down thousands of feet on either side. In a place where communication is essential, the combination of extensive headgear, wind, and language barriers makes this section particularly dangerous.

“There was a dead climber at the bottom [of the path],” said Adams. “My assumption was that he had fallen down the Step and died.” Climbing on the same section of rock, Adams says it was hard not to imagine the same fate for himself.  Photo: Climbers ahead of Adams ascend the Hillary Step, the last section before the summit of Mt. Everest.

Photo: Climbers ahead of Adams ascend the Hillary Step, the last section before the summit of Mt. Everest.

Even with the many challenges facing him, Adams reached the summit of Everest on May 23, 2019. Looking down into the lowlands of Tibet and Nepal with snow swirling around him, Adams’ main concern at that point was just getting back down. Two thirds of the deaths that occur on Everest happen on the way down the mountain. In 1996, eight climbers died in a sudden storm on the way down after reaching the summit.

“It’s a cool experience and one that not many get to have, and [the summit] was incredibly gorgeous, but at the same time, I was absolutely petrified about going down the mountain.”

Adams fortunately made it safely down from the top of the world without any complications, and a year later at 12:34 p.m. on Feb. 27, 2020, exactly 3,160 days since he started the journey, he reached the summit of Mt. Kosciuszko in Australia – The Seventh Summit.

“Looking back on the nine-year journey to complete The Seven, I think about the accomplishment not just for myself but for the type 1 diabetic community, and showing that if you put your mind to it, you can do something great.”

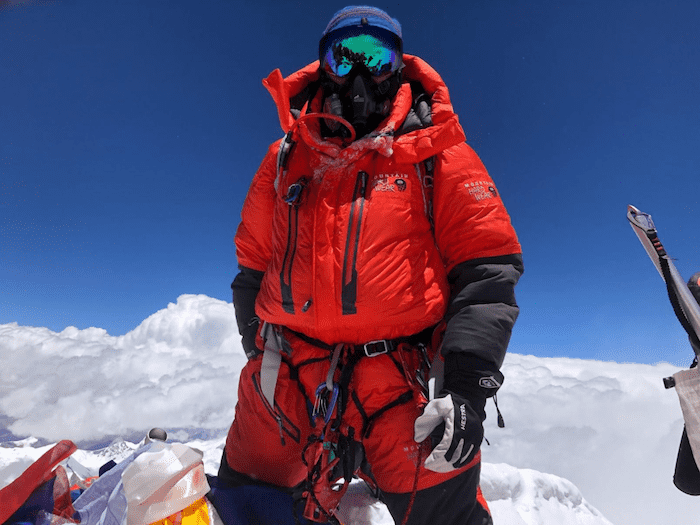

What’s next for Adams? Photo: Adams on the summit of Mt. Everest on his way to becoming the first climber with an insulin pump to reach all Seven Summits.

Photo: Adams on the summit of Mt. Everest on his way to becoming the first climber with an insulin pump to reach all Seven Summits.

Over 10 years after his expedition to Denali, Adams now treats many newly diagnosed kids with diabetes in his role as a pediatric ICU nurse. “I wanted to put myself out there and be a figure that people with diabetes can look up to,” he said. “I thought it would be a great example to show both these children and their families that just having this diagnosis really doesn't need to change what their aspirations are, or what they're able to do in their lives.”

Adams is planning to continue his fundraising and mountaineering journey by climbing Ama Dablam, a 22,000 foot peak in Nepal right next door to Everest.

“It’s not part of The Seven Summits, but I hope to keep raising money,” said Adams. “In the grand scheme of things, the amount of money that I've raised…it’s not a crazy amount of money. But in my role working with critically ill children – a lot of whom are newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes – I think the story that I have is really important to show them that this diagnosis isn't the end of your life. It doesn't define what you can do or who you are going forward.”