How Diabetes Care Can Adapt in a Rapidly Changing World: A Conversation with Dr. Anne Peters

By Frida VelcaniEmily Fitts

By Frida Velcani and Emily Fitts

By Frida Velcani and Emily Fitts

Dr. Anne Peters shares insights on how healthcare professionals can help people ease the challenges of managing diabetes during COVID and how the shift to telemedicine has encouraged greater use of clinical metrics beyond A1C

Dr. Anne Peters, the Director of the University of South California Clinical Diabetes Programs, is one of the world’s leading endocrinologists and an advocate for increased access to quality healthcare. She provides diabetes care to a diverse population in Los Angeles County. Over the last few months, her focus has been on supporting people with diabetes as they deal with additional stress, fear, and uncertainty due to COVID-19. We spoke with Dr. Peters about her experience delivering remote care, the opportunities it has brought, and the challenges she and the people she works with have faced along the way.

Your daily data is “worth a thousand words”

COVID-19 has drastically changed the way people with diabetes live, work, and manage their physical and emotional health. According to Dr. Peters, people may have to manage their diabetes differently depending on how social restrictions have altered their normal routine and surrounding environment (including their proximity to diabetes supplies and access to food throughout the day). Dr. Peters noticed from her practice that eating out less has caused many people with diabetes to have more hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) than usual. In response to these types of lifestyle changes, she has lowered insulin dosing to reduce people’s risk of low blood sugar.

To prepare for a telemedicine visit, Dr. Peters encourages people with diabetes to upload two weeks of blood glucose data from their devices. (You can learn more about uploading your data here.) If a picture is worth a thousand words, you could say the same about a CGM report. The value of the data, according to Dr. Peters, is in the ability to see the hourly and daily variations of blood glucose levels. “I look at all the data – and I love the daily displays – and figure out where the problems are and then fix them. Time in range is an overview for me – the useful data is in the daily data so I can help people make adjustments to improve,” she said.

Dr. Peters is able to draw actionable insights from patterns, particularly glucose spikes after meals or exercise, and adjust medication as needed. For the few people in her clinic with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes who use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), having access to real-time data has been especially illuminating for providing specific therapy recommendations.

She said: “For the people with type 2 diabetes that I can put CGM on and who need it (and oddly everyone needs CGM) – what I’ve done is I’ve ordered it from the pharmacy, and some of the insurers pay for it even if not they’re not on multiple daily injections of insulin (MDI). I [also] have some samples of CGM at home. I send it to people who have prediabetes or drop it off in a bag at their house. I’ve gotten real-time data on all of these people. It’s changed the value in my mind of real-time data.”

With virtual care becoming a new norm for many people with access, Dr. Peters believes even more strongly that every person with diabetes should have access to remote data through a professional CGM at least once a year, or through a 24/7, 365-day personal CGM.

Diving into Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP)

The increasing use and reimbursement of telemedicine, and the loosened requirements for obtaining a CGM, are changing the standards for reported information during a clinical visit. Not only are people with diabetes not physically going to their healthcare professional’s office to get their A1C checked – Dr. Peters also said that using average blood sugar metrics like A1C alone “cannot reveal someone’s lived experience of diabetes.” A report like the Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) uses CGM data to trace average glucose levels by time of day and offers a more nuanced understanding of a person’s diabetes.

Don’t have access to a lab and A1c but have CGM? Look at GMI

The glucose management indicator, or GMI, on the AGP report uses the 14-day average glucose value to provide an estimate of A1C. Since Medicare and many device companies still require that healthcare professionals report A1C, Dr. Peters recommends that healthcare professionals input GMI on the electronic medical record as a proxy for A1C. She believes GMI is the right step forward as it uses more data points to determine average glucose levels and makes more sense logistically since healthcare professionals can look at it alongside estimates of hypoglycemia.

The four most important metrics

At a routine visit, Dr. Peters will mark the following clinical metrics on charts:

-

A1C (if available) or if not, GMI

-

A1C reflects the average levels of blood glucose over approximately three months. Since people have to go to their healthcare professional’s office to get their A1C levels checked, GMI may be a more convenient option for those who are using telemedicine. Many CGM reports will generate GMI based on at least two weeks of CGM data. The Dexcom Clarity report can give you the closest equivalent to an A1C by allowing you to select a time range of 90 days.

-

-

Average Glucose +/- Standard Deviation (SD)

-

Average glucose is an overall measure of blood glucose levels over a period of time. A lower mean glucose often indicates fewer high blood sugars; however, it can also indicate many low blood sugars (hypoglycemia).

-

SD measures how far glucose readings are from the average. For example, if someone has been bouncing around between many highs or lows on a given day, that person will have a larger SD. On the other hand, if someone is having a pretty stable day, that person will have a lower SD.

-

-

Coefficient of Variation (CV)

-

CV measures how far apart glucose values are in general. It provides a lens to look at glucose variability – the ups and downs of diabetes. These can be seen in the small thumbnail representations of your individual days in your AGP or pump report. Generally, most experts recommend a CV of 33% or lower.

-

-

Time in Range

-

Time in range can be used to understand the percentage of time a person is spending in their target range (70-180 mg/dl). However, this value alone cannot tell you if glucose values are skewing high or low. It is important to also consider other metrics such as the percentage of time a person is spending below range (TBR) and above range (TAR). The goal is to shift the numbers into the 70 - 180 mg/dl target window while having fewer lows and extreme highs.

-

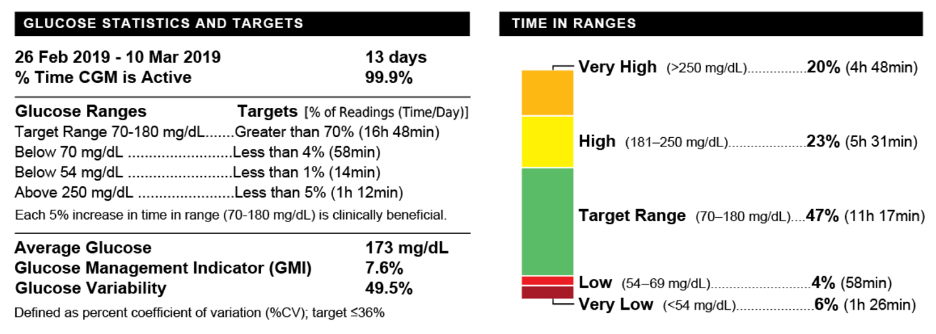

A sample report that shows a summary of glucose values and a set of target numbers.

A sample report that shows a summary of glucose values and a set of target numbers.

As we move through the different phases of lockdown, we can expect them to bring new layers of challenges to people with diabetes as they work to stay in range. “Time in range, glycemic variability, and time spent low and high will all change during periods of stress and isolation,” said Dr. Peters. It’s important to remember that time in range and diabetes management should be individualized. We recommend you speak with your healthcare team about how you can achieve your time in range goals, keeping in mind your unique needs and how the lockdown measures in your city might be affecting your diabetes management.

Opportunities and shortcomings of telemedicine

Telemedicine has greatly reduced the need to travel to seek care, giving people with diabetes more flexibility to schedule doctor’s visits around their jobs and other commitments. The same goes for healthcare professionals who work remotely from home and can use the time saved from travel to see more people. Dr. Peters has seen evidence of this in her own practice. For example, one person with whom she would have routine visits every six months is now able to meet with her every two weeks. Dr. Peters has found these frequent touch points to be especially helpful in fine-tuning diabetes management plans.

At the same time, Dr. Peters recognizes the difficulty of recreating the in-person experience online. “I’m all about the relationship and connection I have with people,” she said, which is why she tries to spend the limited time she has during appointments focused on what people are saying to her. This has undoubtedly made it more challenging to multi-task to record information on their medical charts during the visit.

As telemedicine improves access to healthcare for many people, it is placing a burden on certain populations, including older people with diabetes or people with fewer resources. For example, older adults may have more difficulty uploading data, especially if they are using a CGM receiver instead of a smartphone app. This is where diabetes care and education specialists (DCES, formerly known as certified diabetes educators or CDEs) come in. They play an essential role in helping people with diabetes make the transition to virtual care. By the time Dr. Peters sees someone, they have already spoken to an educator who establishes a bond with them. “One of my educators calls every person the day before their telehealth visit and teaches them how to upload data,” said Dr. Peters. She says that this has positively affected the rate at which people show up to virtual visits.

Dr. Peters reminds us that people with diabetes who have lost their jobs and health insurance coverage are at higher risk for more severe health outcomes – she describes a few specific cases in one of her videos on Medscape. She encourages people to donate money to food banks and to advocate for expanding homeless clinics. “The degree to which we’re going to start seeing people who really don’t have the basics, like electricity,” she said, “will prevent us from reaching out to these people.”

If you are uninsured or underinsured or have recently lost your employee-based insurance, you can learn more about your options for accessing insulin here. For a full list of assistance programs, please see our resource page on paying for insulin. To learn more about access to diabetes care, check out our Access Series, which includes an article on how to get a broad group of diabetes drugs for free.

This article is part of a series on time in range.

The diaTribe Foundation, in concert with the Time in Range Coalition, is committed to helping people with diabetes and their caregivers understand time in range to maximize patients' health. Learn more about the Time in Range Coalition here.