Insights from the ADA Scientific Sessions – Social Determinants of Diabetes Health

By Julia KenneyNatalie Sainz

Social determinants of health describe the interaction between social, economic, and environmental factors and how they can influence a person’s health. Read below for insights from the 81st ADA Scientific Sessions on SDOH and how they impact people with diabetes.

Social determinants of health describe the interaction between social, economic, and environmental factors and how they can influence a person’s health. Read below for insights from the 81st ADA Scientific Sessions on SDOH and how they impact people with diabetes.

Diabetes is an incredibly difficult chronic condition to manage for everyone, but for those who face additional barriers that prevent them from accessing quality and affordable care and education, the challenges are even greater. Issues of equity and access to diabetes care were a central focus of this year's ADA Scientific Sessions. Unfortunately, we know that diabetes does not impact everyone equally because there are many individual, social, environmental, and structural factors that contribute to its prevalence and its outcomes. In order to address disparities in diabetes, it’s important to understand the social determinants of health (SDOH) as factors that can affect its management or prevention. Read below for insights from the 81st ADA Scientific Sessions.

Click to jump down to a section

- What are SDOH? – The socio-ecological model

- Food

- Housing

- Social Vulnerability

- Healthcare

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities

What are SDOH? – The socio-ecological model

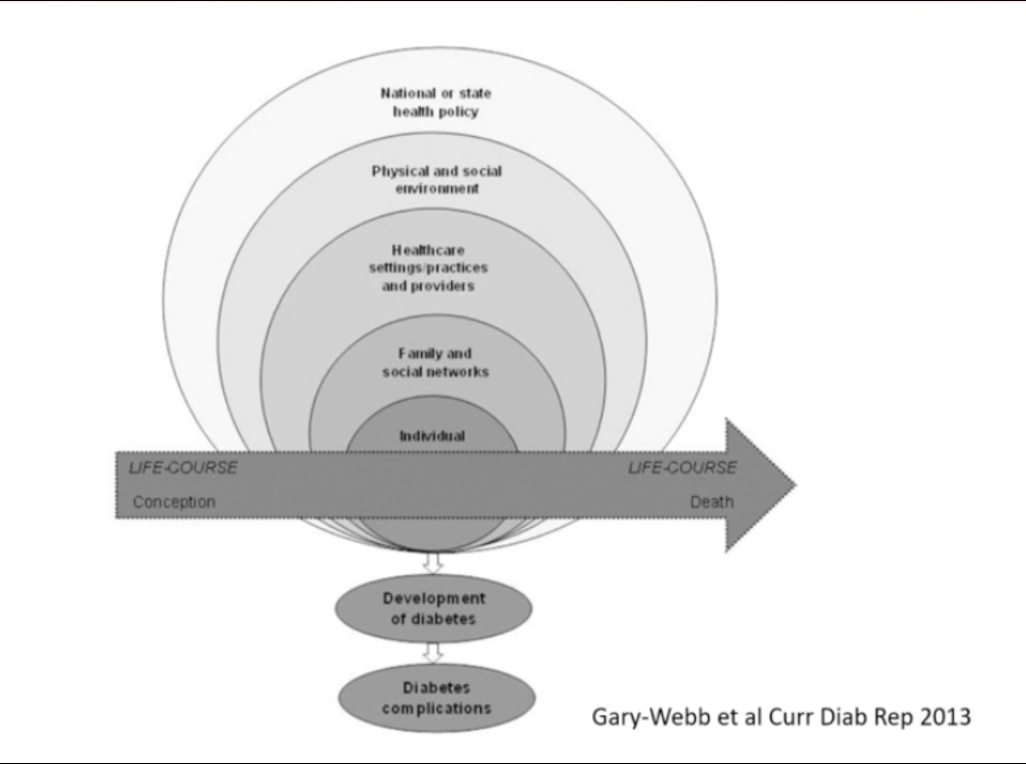

In a presentation on the relationship between SDOH and diabetes, Dr. Shakira Suglia, associate professor at the Emory School of Public Health, described the socio-ecological model, which defines the various levels of SDOH. As you can see in the diagram below, the social determinants fall into different levels of experience – individual, family and social, healthcare, environment, and policy. A person’s experience with the social determinants on these different levels can impact their diabetes management and overall health.

While the socio-ecological model is used to describe SDOH more generally, Dr. Suglia used it to analyze disparities in diabetes. As described in her 2013 paper, the socio-ecological model includes the following levels*:

-

Individual – The first level includes the biological and personal factors that influence a person’s risk for diabetes and related complications. Some examples of these factors include your diet, how much you exercise, smoking habits, internalized stigma, and your socio-economic status.

-

Family and social networks – The second level identifies factors related to your family and social networks, which can influence you to adopt both positive and negative health behaviors. According to Dr. Suglia, “Individuals are nested within social networks of families and friends, and they are influenced by the behaviors of members of their network.” For example, social support from friends and family can make diabetes management easier, but too many social obligations can take time away from diabetes management and self-care.

-

Healthcare settings/practices and providers – The third level describes factors related to your ability to access quality healthcare. These factors don’t correspond to specific treatments, but instead fall under general healthcare. Social determinants on this level include your insurance coverage, healthcare costs, structural racism in the medical community, and your relationship with your healthcare team.

-

Physical and social environment – The fourth level describes factors associated with your environment and even the neighborhood you live in that can influence diabetes prevention and management. For example, individuals living far away from a grocery store lack access to highly nutritious foods, making it more difficult to eat healthy and prevent or manage diabetes. Food scarcity can also impact social and cultural food practices, increasing a neighborhood’s reliance on fast foods and unhealthy diets that increase your risk for diabetes. Other factors include access to green space, social stigma from your peers, and neighborhood safety.

-

National or state health policy – The fifth level describes policy interventions. Some policies prevent successful diabetes management, such as discriminatory policies against people with pre-existing conditions. Other policy interventions support diabetes management and prevention, such as the National Diabetes Prevention Program and Insulin Copay Caps. Health-related policies, and those that influence other SDOH such as housing, food, and income, can have major impacts.

Dr. Suglia said that the factors in all five levels can lead to, or prevent, diabetes and related complications. Most social determinants fall into more than one level on the socio-ecological model, and they can interact with one another in many different ways.

*The socio-ecological model is used in many disciplines, and the levels are defined differently depending on the subject and research.

Understanding these different levels highlights how complex health really is. All people, including people with diabetes, need access to basic life necessities – food, water, housing, healthcare, and social support. By increasing access to these important resources, we can more effectively address health disparities.

Food

Everyone needs access to a nutritious diet to stay healthy, especially to help prevent and manage diabetes. In a presentation on food insecurity, Dr. Seth Berkowtiz from the University of North Carolina described this problem and its impact on people with diabetes. According to the USDA, a person is food insecure when they lack “consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, one in six (over 5 million) people with diabetes were food insecure in the US, which is roughly 1.5-2 times greater than the national rate. Because national food insecurity rates increased exponentially during the pandemic, food insecurity among people with diabetes has likely gotten worse.

People with diabetes often experience food insecurity when they don’t have enough money to pay for food along with other expenses such as housing and healthcare. Dr. Berkowitz said that food insecurity also stems from issues such as not having a healthy selection of food at your local grocery store, not having a car to go get groceries, or not being able to store fresh food in your home. Dr. Berkowitz described the following evidence-based ways that food insecurity leads to worse diabetes health outcomes:

-

Nutritional – Food insecurity limits dietary options, forcing people to eat unhealthy foods that worsen diabetes outcomes.

-

Compensational – Limited financial resources forces people to choose between paying for food or paying for healthcare.

-

Psychological – Food insecurity can lead to depression and anxiety, making diabetes management more difficult and increasing diabetes distress.

People who are food insecure have 1.5-2 times greater odds of having an A1C greater than 9%, Dr. Berkowitz said. Food insecurity is also associated with worse LDL (or “bad”), cholesterol control, and increased rates of diabetes complications such as heart, eye, and kidney disease. People of color and low-income individuals are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity and are also at the greatest risk of developing diabetes-related complications.

Housing

It is notoriously difficult to measure the exact number of people who experience homelessness in the US given a number of difficulties, as a result, researchers have developed a method in which they conduct what is called a “Point-In-Time count”. This method attempts to count the total number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night each year in order to estimate roughly the total homeless population. According to the 2020 Point-In-Time count, researchers counted more than 580,000 people experiencing homelessness in the US, and estimate that 2-3 times that number are homeless at some point throughout the year. In a presentation on homelessness and diabetes, Dr. Margot Kushel from the University of California, San Francisco spoke about the barriers homeless people face in disease management and said that homelessness stems from a series of social determinants, including affordable housing availability, income inequality, mental health disabilities, substance use disorders, and the strength of the social safety net (subsidized housing, healthcare, etc.).

Rates of diabetes among the homeless population are staggering. In the US, 22% of homeless people have diagnosed diabetes compared to 10.3% of the general population. These numbers are likely much higher than reported because diabetes is severely underdiagnosed among the homeless.

The homeless population is aging, and the proportion of homeless individuals over age 65 is projected to triple by 2030, Dr. Kushel said. This will likely lead to increased rates of diabetes among homeless individuals, she said, as diabetes risk increases with age.

“Without stable housing, everything falls apart,” Dr. Kushel said.

In addition, homeless individuals often face barriers to good food, healthcare, and social support, making diabetes prevention and management extremely difficult. For example, many homeless people cannot receive mail, limiting access to important health-related documents or mail-ordered medications. Homeless individuals also experience stigma and discrimination that can harm their mental and physical health.

Social Vulnerability

Even for those who do have housing, your ZIP code can be a strong predictor of health. Dr. Shivani Agarwal called this “social vulnerability,” describing it as, “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” Some environments make it exceedingly difficult to manage diabetes, while others help support it. Having a safe living space that supports positive health behaviors is a key component to managing and preventing diabetes.

Brittany Smalls from the University of Kentucky gave the following examples of environmental factors that can have a large impact:

-

High walkability in a neighborhood is associated with low incidence and prevalence of diabetes.

-

High exposure to greenspace is associated with low incidence of diabetes.

-

Air pollution is associated with increased diabetes risk and the development of cardiovascular disease and stroke in people with diabetes.

-

Higher neighborhood social cohesion (a strong community) has been associated with 22% lower incidence of diabetes.

Healthcare

As expected, access to healthcare is one of the most important SDOH for people with diabetes. Diabetes is a complex chronic condition that often incorporates many therapies, devices, and care specialists. Without consistent access to healthcare, diabetes can be nearly impossible to manage.

Over 30 million Americans (12%) were uninsured in the first half of 2020. An additional 21% of Americans were underinsured, meaning they had unaffordable healthcare plans with high deductibles and/or premiums. A lack of health insurance coverage is associated with worsened glucose management and higher rates of undiagnosed diabetes, which can lead to serious health complications. Inadequate insurance coverage also limits diabetes prevention efforts because people cannot afford regular visits to a healthcare provider.

Dr. Frank Wharam, an Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School, discussed the history of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and its impact on insurance coverage in the US. In 2010, 33% of people with diabetes were uninsured. After the ACA was passed, the rates of uninsured people with diabetes in the US dropped to 6%. According to Dr. Wharam, the ACA helped bolster healthcare for people with diabetes in the following ways:

-

It expanded access to Medicaid for low-income individuals.

-

It increased subsidies for federal marketplace health plans.

-

It helped make therapies more affordable for people on Medicare.

-

It required free preventive health services, including screening for type 2 diabetes and nutrition counseling.

-

It increased the dependent eligibility age so that people can be covered under a parent or guardian’s health plan until age 26.

-

It outlawed coverage discrimination against people with pre-existing conditions.

Check out diaTribe’s Access articles to learn more about ways to save money on diabetes care and medications.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

We know that diabetes does not affect everyone equally. People of color and low-income individuals have disproportionately low access to food, housing, and healthcare and are subsequently the most adversely impacted by diabetes. In addition to higher rates of diabetes, communities of color are more likely to experience serious health complications. Hispanic, Black, Asian, and Native American individuals receive, on average, lower quality of diabetes care, compared to white individuals, which can lead to increased complications and mortality.

Diabetes in American Indians and Alaska Natives

Dr. Yvette Roubideaux of the National Congress of American Indians discussed how diabetes has impacted American Indian and Alaska Native communities. During the 1990s, researchers identified an urgent need for intervention as diabetes prevalence and mortality increased significantly in these communities. The diabetes-related mortality rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives was 3.5 times that of the US population. Studies have shown since then that diabetes prevention efforts have helped reduce diabetes prevalence and complications, though disparities still exist.

Dr. Roubideaux described the positive impact that the Special Diabetes Program for Indians (SDPI) had on American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Congress established the SDPI in 1997 to provide funding and resources for diabetes treatment and prevention to Indian health programs across the US. The budget since 2004 has been set at $150 million per year. The SDPI focused on increased access to quality diabetes care, implementation of evidence-based practices, and adapting care to align with the cultural norms of each community. This approach also emphasized the importance of allowing communities to tailor their health intervention programs. As a result, diabetes services in American Indian and Alaska Native communities significantly increased from 1997 to 2019. Among SDPI healthcare sites, the presence of a clinical team that provides diabetes treatment and prevention services went up from 30% in 1997 to 95% in 2019.

Since the start of the program in 1997, American Indians and Alaska Natives decreased their average blood sugar by 10% and reduced their cholesterol by 24%. Overall, Dr. Roubideaux said that Native American communities were able to significantly improve control of glucose, cholesterol, and average blood pressure over a 20-year period. Further, severe diabetes-related complications decreased; hospitalizations for poorly managed diabetes decreased by 84%, and new cases of kidney failure decreased by 54% in adults, a decline even more considerable than other groups across the US.

Diabetes prevalence among Native populations in the US has continued to decrease over the last decade, going from 15.4% in 2013 to 14.6% in 2017. Diabetes mortality also decreased by 37% over this time. While the SDPI and other interventions have undoubtedly helped address the diabetes epidemic in Native communities, disparities are still prevalent. American Indians still have the highest prevalence of diabetes of any other racial/ethnic group in the US. Learn more about racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes here.

The social determinants of health are a means to understand the factors that impact diabetes management and prevention. We can also use SDOH to help address the inequities that still exist today. Without a holistic approach, the diabetes epidemic will continue to grow.

Stay tuned for more insights from ADA on policy interventions for people with diabetes.