Low Carb vs. High Carb II – My Diabetes Diet Battle Continued

By Adam Brown

Tripling my carbs --> 5 fewer hours in-range per day, 64% more insulin (!), & more lessons learned.

by Adam Brown

I’ve discovered a therapy that:

I’ve discovered a therapy that:

-

Keeps my blood sugar in range ~75-95% of the time with a low risk of hypoglycemia;

-

Uses ~30-65% less insulin;

-

Cuts my odds of taking the wrong dose of insulin and experiencing severe hypoglycemia;

-

Requires less time spent on diabetes tasks;

-

Eliminates lots of diabetes anxiety, frustration, and feelings of failure;

-

Keeps my blood pressure, cholesterol, and weight in a healthy range;

-

Counters what I was told at diagnosis, what the average diabetes diet looks like, and what the food environment encourages me to eat.

And it’s only three words: eat fewer carbohydrates.

I’ve been doing this for about six years now, and my Low Carb vs. High Carb article last fall showed some of these takeaways in a 24-day self-tracking experiment. Doubling my carb intake led to the same average blood sugar, but four times as much hypoglycemia, 34% more insulin, and a lot more diabetes work and feelings of failure.

Since then, I’ve been dying to repeat the same experiment, but with two key tweaks: (i) eating even lower carb (to get more separation between the two phases); and (ii) dosing insulin slightly less aggressively during the high-carb phase (to cut the hypoglycemia).

This article documents what happened after I tripled my carb intake, comparing six days of ~106 grams per day (“low carb”) to six days of ~331 g per day (“high carb”), or 15% vs. 50% of my daily calories from carbohydrate. For comparison, last fall I roughly doubled my daily carbs: 12 days of 146 g per day vs. 12 days of 313 g per day (21% vs. 43% of daily calories).

The topline results were similar to version one, but even more in favor of low carb this time:

-

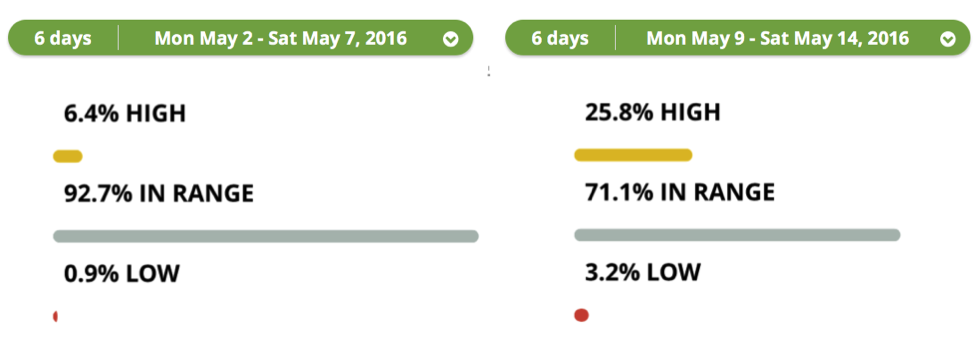

On low carb, I spent five more hours per day in range (70-150 mg/dl): 93% of the time compared to 71% on high carb.

-

Time spent high quadrupled on high carb, while hypoglycemia was similarly low in both phases.

-

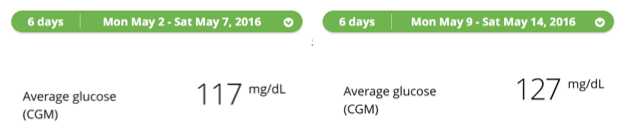

My average blood sugar was 10 mg/dl higher on high carb (117 vs. 127 mg/dl), equating to an estimated 0.4% increase in A1c.

-

High carb required 64% more insulin every day. I also needed more bolus insulin for each high-carb meal (10-15 units) than for an entire day eating low carb (10 units).

The round two glucose and insulin results are shown below in more detail, followed by five more fascinating lessons learned: insulin-dosing danger, extreme blood glucose levels, why the low-carb results are better this time, eating out, and the impact of calories. I’ve also added some thoughts for people with diabetes and healthcare providers. You’ll find strengths, limitations, and more notes on setup in the appendix.

My greatest hope is for the diabetes community to more expansively evaluate the pros and cons of different dietary approaches – the impact on glucose (time-in-range, hypoglycemia, variability), insulin-dosing danger, diabetes burden and stress, and quality of life. Low-carb eating helps me balance all those factors like nothing else I’ve ever tried. I would love to hear your feedback by email or on Twitter!

[Editor’s Note: You should talk to your healthcare provider before making any significant changes to your own diet, medications, or routine.]

|

|

Low Carb II |

High Carb II |

|

Daily Carbs |

106 g |

313 g |

|

Average Daily Calories |

2,910* |

2,657* |

|

Calorie Breakdown |

15% Carb |

50% Carb |

|

Primary Foods |

Vegetables, nuts, seeds, olive oil, eggs, chicken, fish, lean beef, and high-fiber/low-carb tortillas. |

Fruit, whole wheat bread, brown rice, pasta, oatmeal, granola, eggs, chicken, vegetables. |

* I address the calorie discrepancy in lesson #5 below.

** See the Appendix for more notes on setup.

This lower-carb diet was nowhere near Atkins level (20 grams per day), and the higher-carb diet was roughly consistent with the “average” 45% carb diet in people with diabetes (according to ADA).

Round Two Results

Glucose Profiles

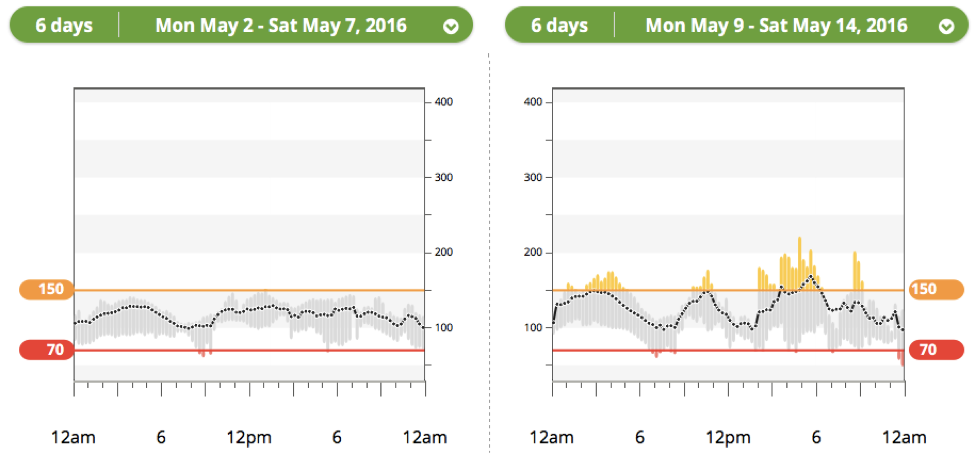

The plots below show my daily glucose profiles averaged over six days of high-carb II vs. six days of low-carb II. The black line shows the average at that time point, while the bars indicate the range of values at that time (yellow=high, gray = in range, red = low). Can you guess which is high carb and which is low carb?

|

Low Carb II |

High Carb II |

|

|

These results are very similar to my previous experiment, with two caveats: the low-carb results are slightly better overall, while the high-carb results are more troublesome in the afternoon.

Time-in-Range

My blood glucose stayed in range 93% of the time on low carb, a sizeable advantage over 71% for high carb. That translated to five more hours (!) every day in the zone of 70-150 mg/dl on low carb (left side). This was better than I expected and I unpack it further below.

Hypoglycemia was quite low in both periods, though it was once again greater on high carb. At 3% this time, however, it was half of last fall’s 6.8% (my stated goal). My time spent high quadrupled during the high carb II phase.

Average Glucose

Average glucose was +10 mg/dl higher on high carb this time, an estimated ~0.4% increase in A1c. This was slightly different from my previous experiment, where I achieved a similar average glucose in the two phases: 123 vs. 121 mg/dl. Two factors probably played a role in the higher average during high carb: (i) eating a slightly larger percentage of my calories from carbs this time; and (ii) the natural tradeoff to having half as much hypoglycemia.

These high-carb glucose results are still very solid: 71% of the day in-range, with an average blood glucose (127 mg/dl) that predicts an A1c of 6.1% - far better than I did as a teenager!

In comparison, however, the low-carb results are substantially better by every metric: more time-in-range, one-third as much hypoglycemia, a lower average glucose, 64% less insulin (see below), and less time and frustration spent on diabetes.

Insulin

I needed 64% more insulin on the high-carb diet this time, as my bolus insulin tripled to cover the three-fold increase in carbs.

|

|

Low Carb |

High Carb |

|

Total Daily Dose |

33 units |

54 units |

|

Bolus |

10 units |

31 units |

Last fall, my bolus insulin doubled, and my overall insulin was 34% higher – very consistent results. I did not change my daily basal insulin (23 units) between the periods, similar to my approach in round one. The bolus insulin data confirms that I was not under-dosing insulin on high-carb – the three-fold increase in bolus insulin is what would be expected when tripling carb intake.

Lessons Learned II

1. Eating high carb magnifies the dangers of dosing insulin. Meals with 100+ grams of carbs needed more bolus insulin in one dose than I use in an entire day eating low-carb. The difference between an in-range blood sugar and severe hypoglycemia can be just a few units, and when estimating bolus doses of 10-15 units at a time for many high-carb meals, these errors are so easy to make. I would much rather make a 30% dosing error on a low-carb bolus of 2 units vs. a high-carb bolus of 10-15 units – the risks of getting it wrong are dramatically lower.

Put differently, there is nothing “magic” about a low-carb diet; it simply removes many sources of variability and decreases the odds of taking a wildly inaccurate dose. Errors of 30%-50% are realistic after factoring in everything that influences blood glucose and how much insulin to take: carb counting error; pre-meal insulin timing (20 minutes before vs. at meal start); variable insulin absorption (e.g., injection site); variable glucose absorption (e.g., glycemic index, fat, fiber); activity; changes in insulin sensitivity from day to day and within each day; glucotoxicity (insulin resistance from a higher blood glucose); and at least 15 other things. For me, a low-carb diet minimizes or eliminates the influence of many of these factors, which is why it seems to improve my glucose AND decrease my diabetes burden.

-

Following this experiment, I’m also terrified to think about the average-case or worst-case scenarios that typically happen on high-carb diets: blind bolusing (not measuring blood glucose or wearing CGM); missed meal boluses; eating more processed foods with a lot more sugar; hypoglycemia unawareness, etc. Under these very common circumstances, taking 10 and 15-unit boluses could be downright dangerous. Low-carb diets can help defend against many of these worst-case scenarios – e.g., a missed bolus is not as big of an issue when eating few carbs, eating processed foods is less likely on a low-carb diet, monitoring is less mission critical with fewer carbs (glucose fluctuations are less severe), etc.

-

When we evaluate different diets, I think we should take the insulin-dosing danger into account. The ADA’s nutrition recommendations note that evidence is lacking to recommend a specific number of carbs per day. That may be true when measuring the effectiveness of different diets from an average A1c or weight perspective, but I hope we can think on a more personalized level: what might low-carb diets offer to different individuals?

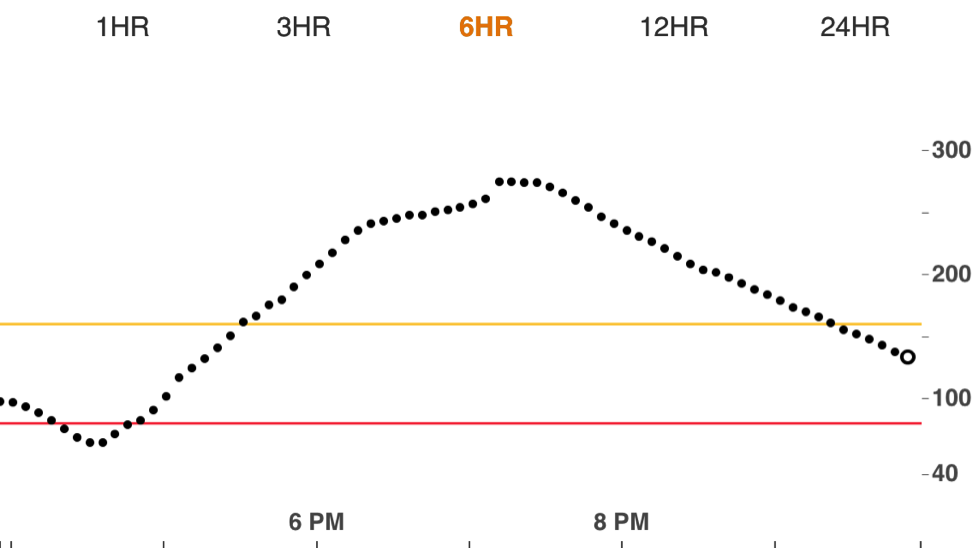

2. Diabetes is a battle of staying in range, and high-carb days made extreme blood glucose levels (over 250 mg/dl) a near-certainty. In both experiments combined (36 days total), two out of every three high-carb days had a blood glucose over 250 mg/dl – arguably a best-case scenario, since I measured all carbs out, ate unprocessed food, dosed insulin 20 minutes before eating, and continuously added insulin based on my CGM trend and insulin-on-board. By contrast, I had zero low-carb days with a blood glucose above 250, and that was with insulin doses taken at the meal start or not at all.

% of Days with a Blood Glucose over 250 mg/dl

|

Low Carb |

High Carb |

0%(0 out of 18 days) |

67%(12 out of 18 days) |

A low-carb diet helps minimize excursions and maximizes the probability of staying in range for more of the day. Conversely, extreme highs take hours to recover from. Look at this example from a high-carb excursion to 275 mg/dl. I spent nearly four hours above range – even after doing as much as possible with my insulin dosing to stay in range.

-

This could speak to “glucotoxicity” – high blood glucose levels can cause insulin resistance, making it far harder to come back down (or as I like to say, “When it rains, it pours. Ugh!”). One of the big reasons I find low-carb helpful is it minimizes these big excursions.

3. How did I spend 93% of my low-carb days in-range, an 11-point improvement from last fall? – fewer carbs, more fiber, and earlier dinners without much nighttime snacking. In comparing these new lower-carb results to last fall, the 11-point gain in time-in-range (93% vs. 82%) came completely from reducing time spent high (6% vs. 17%). I believe three factors helped:

-

A further 32% reduction in carbs: I went from 146 g of carb per day (low carb I) to 106 g per day (low carb II). Carbs increase blood glucose far more than fat or protein, so it’s not surprising to see my time-in-range improved with fewer carbs.

-

More fiber: 55% of my carbs came from fiber in low-carb II (58 g per day), up from only 30% last fall (44 g per day). Fiber does not impact blood glucose significantly, and it has the added advantage of blunting post-meal glucose spikes. The additional fiber (above nuts and vegetables) came from two new sources: low-carb/high-fiber tortillas & chia seed pudding (both discussed in my Homerun Breakfast column).

-

Earlier dinner, little or no snacking near bedtime: Following my breakfast article, I’ve also been trying to eat an earlier dinner without a subsequent snack – it makes a huge difference for improving overnight and next-morning blood glucose values. This tactic contributed a bit to the results in this round, since both phases had better overnight and morning blood sugars vs. last fall.

4. Eating out is often more manageable on a lower-carb diet. I ate the following two restaurant meals during this experiment: half a plate of vegetables with a chicken breast vs. a big plate of brown rice with veggies. The high-carb rice meal was so much tougher to bolus for, since the pile of rice could have been two cups, or three cups, or 1.5 cups (90 g, 135 g, or 60 g of carbs). I took my best guess and crossed my fingers I had it right. By contrast, a big plate of vegetables with a piece of chicken is an easy bolus – almost always 1-2 units, and no need to “carb count.”

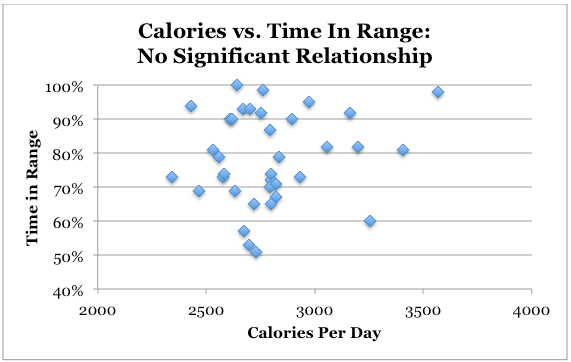

5. Calories were not associated with time-in-range – even though I ate ~250 fewer per day in high-carb II. As noted in the initial table, I ate 2,910 calories during low-carb II vs. 2,657 during high-carb II. This was unintentional, but as you saw above, it didn’t give high-carb any big glucose or insulin advantage at all (nor did it change my weight). The graph below supports this assertion with more data, comparing calories per day to time-in-range from all 36 days. My takeaway: no clear relationship between calories consumed and time-in-range in these trials.

So if I’m trying to lose weight, is a high-carb, whole grain diet better? While low-carb diets are higher in fat (and thus, more calories per gram), there are many things to consider:

-

Weight loss is not as simple as calories in-calories out. Watch this lecture by Gary Taubes, or read his outstanding books (Good Calories, Bad Calories; Why We Get Fat) and NYT articles (Diet Advice that Ignores Hunger; What if It's All Been a Big Fat Lie?). Read this excellent Atlantic article by Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley for some of the measurement nuance and history of calories. For instance, the number of labeled calories in foods like almonds over-reports what the human body actually absorbs! See our recent article on The Biggest Loser for a biological view on this topic.

-

More insulin and hypoglycemia on a high-carb diet might drive weight gain in some individuals. Read the Q&A from last fall for more on this topic.

-

Last fall, I actually ate more calories during high-carb, so it’s not a given that low-carb is lower calorie.

-

Low-carb meals often include more fiber and more protein, which can make them more filling than high-carb meals.

Messages to People with Diabetes

-

Track how many carbs you eat per meal and in a day with an app like LoseIt! or just pencil and paper.

-

How do your blood sugars vary depending on the number of carbs you eat?

-

How does the burden of managing diabetes change with more vs. less carbs?

-

Is insulin dosing harder or easier when eating less carbs?

-

How differently do you feel when you eat more or less carbs?

If you decide to change to a low-carb diet, do so slowly. It takes the body time to adjust to a very different diet, and you may need drastic changes in your insulin doses. I would recommend starting with just one low-carb meal per day (my choice would be breakfast) – and of course, let your healthcare provider know you are doing this.

Messages to Healthcare Providers

Imagine a therapy that could keep your patients in range for more of the day, reduce the hassle of diabetes, substantially decrease insulin needs, and dramatically cut the dangers of dosing insulin. Is that a therapy worth trying?

A1c and average glucose are not the only metrics to determine if a diet or therapy is effective. We should take into account insulin-dosing danger, time-in-range, hypoglycemia, variability, extreme blood glucose values, and the mental and emotional burden different diets impose on people with diabetes (e.g., carb counting, insulin calculations, worry, anxiety, fear, etc.).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not the only standard for establishing the evidence of an intervention. As someone who studies science every day, I recognize that the “plural of anecdote is not data.” I’ve done my best to be scientific in these carb experiments, but by no means are these robust trials. On the other hand, I think it would be a disservice to wait for long-term RCT evidence to tell us what diet is most effective for diabetes. We may never have it. (Digression: no RCT exists to prove that parachutes save lives, and no one would argue we should run one.) What level of evidence do we need to show that low-carb diets are effective for some people with diabetes?

Read this fascinating editorial from Nutrition: “Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base.”

Experiment Strengths

-

Careful, objective measurement of glucose (CGM), insulin (pump), carbs and calories (LoseIt!), activity (Fitbit)

-

Insulin doses taken 15-20 minutes before all high-carb meals

-

Unprocessed, whole foods in both low- and high-carb phases

-

Use of real-time CGM trends to continuously add insulin on the fly (when insulin on board would be insufficient to bring blood glucose back to 100 mg/dl)

-

Consistent results between last fall and this experiment (now 36 days of data)

-

High-carb results were still better than ADA recommended goals for therapy

-

Very real-world experiment

Limitations

-

N=1 – are these results replicable and generalizable?

-

Short duration – how would these results look over a lifetime?

-

No insulin settings optimization during high-carb – would I have done better with a different basal rate or insulin:carb ratio?

-

Less experience dosing insulin for high-carb meals – with more practice I might have done better.

-

Not a blinded experiment – I knew which phase I was in at all times.

-

Calories and activity were not perfectly equal between each phase.

Concluding Thoughts

Eating low-carb is the single most important decision I’ve ever made for managing my diabetes. A lower-carb approach requires some tradeoffs (convenience, variety, time) that may not be worth it for everyone. But for me, it’s a gamechanging therapy unlike any other I’ve tried.

Questions?

See this Q&A for answers to questions received last fall, and please send others by email or on Twitter!

[Editor’s Note: This article should not be interpreted as medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider before experimenting with significant changes to your diet, insulin, or medication regimen.]

Appendix 1: How Did I Collect Data and Avoid Hypoglycemia During High Carb?

I used the same food, data collection, and insulin-dosing methods previously described: glucose data from Dexcom CGM (G5 and Clarity), measuring carbs and tracking food data with the excellent LoseIt! app, dosing insulin 15-20 minutes before high-carb meals, and adding insulin post-meal when I didn’t have enough on board to bring me back down to 100 mg/dl. I’ve used screenshots from the downloads wherever possible.

To reduce hypoglycemia in round two of high carb, I did two things: (i) paid more careful attention to insulin-on-board (no stacking insulin!); and (ii) increased the duration of insulin action from my standard 2.5 to four hours. The latter more accurately reflects how long large high-carb boluses (5-12 units) continue to lower blood sugar. I find a shorter duration of action (2.5 hrs) works well for small low-carb boluses (1-3 units).

Appendix 2: What Foods Did I Eat?

Low Carb Meals: I’ve described my low-carb diet in depth in a previous column. It’s a lot of nuts and seeds, vegetables, chicken, fish, and eggs.

High Carb Meals: My high carb meals relied on whole foods: old fashioned plain oatmeal; whole wheat bread or bagels; fruit; brown rice; whole wheat pasta, etc. I wanted to isolate the impact of higher carb intake, so keeping the food healthy was essential – adding junk food would have confounded the experiment.

Appendix 3: Did Activity Play A Role?

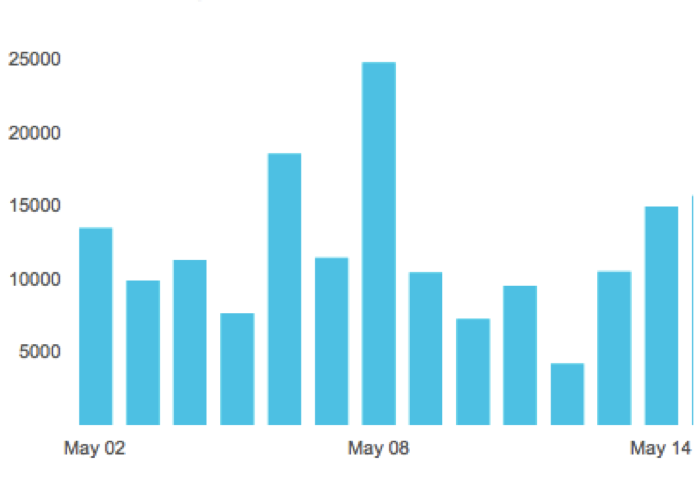

As measured by my Fitbit, I averaged 12,079 steps per day during low-carb II vs. 9,506 steps during high-carb II. That sounds like a large difference in average activity, but it isn’t tremendous – 2,573 steps per day is the equivalent of a 20-minute walk, or about the distance of my daily commute to work. If you read my experiment last fall, the trend went in the opposite direction: I walked 1,852 steps more on the high-carb diet, and the glucose results were similar to this round. It would have been ideal to have identical steps between all the low-carb and high-carb stretches, but the tradeoff would have been a less real-world experiment. The additional steps per day on low-carb II may have helped my blood glucose a bit, but it was far less significant than the impact of eating more carbs. When I ran the statistics, 54% of the variation in time-in-range was explained by carbs per day vs. just 9% for steps per day.