Salt, Sugar, Fat: A Food Culture in Need of Change

.jpg) by James S. Hirsch

by James S. Hirsch

Years ago, in one of his stand-up routines, Jay Leno told of how he saw a can of “Cheez Whiz” at a convenience store.

“Here’s what I want to know,” Leno said. “How much ‘whiz’ is in ‘Cheez Whiz’?”

A better question nowadays might be: “How much ‘cheese’ is in ‘Cheez Whiz’?”

The answer: not much, and maybe none at all. It had real cheese when it was introduced in 1953, but cheese is no longer listed as an ingredient – a reformulation, apparently, to boost profits, if not taste. The food scientist who invented the spreadable says it now tastes like “axle grease.”

In Search of the “Bliss Point”

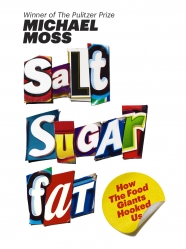

So reports Michael Moss in Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. An investigative reporter for The New York Times, Moss takes long, relentless aim at processed foods and sugar-sweetened sodas, through which the unholy trinity of health hazards (salt, sugar, fat) is poisoning our diet. The villains in this tale are the mega food companies that shamelessly market their products to children, misrepresent or deceive with their labeling, and spare no expense to bring consumers to their “bliss point.” No, that is not a reference to a spiritual epiphany or sexual ecstasy, but something better – as Moss writes, “the precise amount of sugar or fat or salt that will send consumers over the moon.”

With brain scans showing that humans are hard wired for decadent foods (so are rats), we are at a massive neurological disadvantage in resisting Krispy Kremes and Big Gulps and Frosted Flakes. Food companies, Moss explains, have “discovered that the brain lights up for sugar the same way it does for cocaine.”

Propelled by an excerpt in the Times, Salt Sugar Fat became an instant best-seller, and Moss himself has made the media rounds to explain how food makers and their lobbyists, in cahoots with supermarkets and with the acquiescence of government, are seducing us to put ever more empty calories into our bodies. “There is nothing accidental in the grocery store,” Moss writes. The processed foods and sugar sodas “are knowingly designed – engineered is a better word – to maximize their allure.” The title of Chapter 1: “Exploiting the Biology of a Child.”

Implications for Diabetes

Is any of this relevant to the diabetes world? I think yes. Food, of course, plays a central role in the disease, as our high-calorie culture has contributed the obesity epidemic that is driving type 2 diabetes while complicating the efforts of anyone with diabetes to maintain normal blood sugars. By focusing on the apparently addictive properties of processed food – and the willful efforts by companies to manipulate those properties – Salt Sugar Fat shifts responsibility away from the individual and implies that more direct intervention by government is necessary. The book is part of a slow but growing movement, evidenced most recently by New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to change our acceptance of junk food as an immutable fixture of our nutritionally deprived landscape. If that ever happens, the diabetes world would be the better for it.

Free Candy

A quick anecdote: My hometown outside of Boston has a Walgreens, and like any retail drugstore, it displays all kinds of candy and wrapped cookies, brownies, or even cupcakes right next to the cash register. You can’t buy anything in this Walgreens without being tempted to purchase its most unhealthy products. Fair enough. We live in a free country with free markets, and if this is how Walgreens wants to maximize its profits, so be it.

But last year Walgreens began offering a promotion: “buy one candy bar, get a second one free.” The cashier, in fact, encouraged me to take advantage of the free candy. It is one thing to make Hershey bars cheap and accessible, but now the drug store is literally giving them away. Which raises a question: if a convenience store had that same promotion for a pack of Marlboros, or if a liquor store had that promotion for a bottle of Jim Beam, what would the response be? I suspect, outrage. We will permit those sales of tobacco and liquor to qualified buyers, but any seller who tried to give them away for free would be pilloried, and it would be bad for business.

That is the subtext to Salt Sugar Fat. The volume itself doesn’t really break new ground. Other books have described the transformation of our foods through a blend of sophisticated food science and brilliant marketing, combined with an understanding of how our brains and emotions work. Salt Sugar Fat hews closely to that science, but what stands out is how deeply it reaches into the companies themselves in explaining their dogged efforts to increase consumption of Banana Split Crème Oreos and Chocolate Marshmallow Kisses and Stacy’s Cinnamon Sugar Pita Chips.

Getting Addicted to Salt

For example, Frito-Lay’s former chief scientist showed how the company used mathematical equations to manipulate the high salt and fat content in chips to create the “ideal snack” – ideal for sales, that is, not health. (“People get addicted to salt,” the food scientist acknowledges to Moss.) Scientists at Nestle are fiddling with the distribution and shape of fat globules to affect their absorption rate and “mouth feel.” Self-delusion also seems part of the mix. The inventor of Oscar Mayer’s “Lunchables,” a nutritional disaster for children, showed Moss the company records that described the fat-laden meat and cheese with innocuous terms like “product delivery cues.”

Then there is Cargill, which is altering the physical shape of salt so it hits the taste buds faster, improving what the company calls its “flavor burst.” Cargill, in fact, earns the trifecta – it is the world’s leading provider of salt and also produces sugar and fat. And with $134 billion in annual revenue, it sells them all with zeal. So promiscuous is the overconsumption of its products that by the time Cargill is introduced in the book, it might as well be selling nuclear missiles to the Taliban.

The country’s overall nutrition numbers tell the story: Americans now eat 33 pounds of cheese and cheese products per year, per person, which is triple the consumption rate of the 1970s. We now consume 22 teaspoons of added sugar a day, three times as much as we did in 1970.

The Tobacco Model

So where does that leave the diabetes community? For all the evidence he’s marshaled, Moss himself does not offer any real recommendations, beyond saying that we have the power to buy these products or not buy them. The deeper question is whether salt, sugar, and fat will ever occupy the same place in our consciousness as tobacco – products deemed worthy of restriction and subject to special taxes or other punitive measures to reduce consumption.

The challenge, compared to tobacco, is obvious. Cigarettes are a discreet, identifiable item smoked for pleasure. Once a national consensus emerged that they were addictive and should be restricted, the policies to curb advertising and sales were relatively easy to implement. Salt, sugar, and fat, however, are all necessary to survive. It is their overconsumption that is dangerous. You could ban the advertisement on kids’ TV shows of, say, Coke and Snickers, but what about potato chips, fruit juices, and McDonald’s? They can be just as unhealthy.

Any government intervention would necessarily be arbitrary – and that is precisely what undid Mayor Bloomberg’s effort to ban in New York sugar sodas larger than 16 ounces sold by restaurants, movie theaters, push carts, and sports areas. A Manhattan judge ruled the policy “arbitrary and capricious.” The outcome was also a reminder of the power of the food and beverage industries, which opposed the ban. The mayor vows to fight on.

Recommendations for Change

Not all is lost. A former Kraft executive named Michael Mudd, whose efforts to reform his company were featured in the book, believes we have several options to improve the quality of our foods. As he recently wrote in The New York Times, we could make the following changes:

Levy federal and state excise taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages and a few categories – snack foods, candy, sweet baked goods – that most undermine health. (He doesn’t say how such a tax would be implemented.)

-

Federal guidelines for marketing food to children were proposed as voluntary in 2011 but, thanks to food industry lobbyists, they were blocked by Congress. Revive those guidelines and make them mandatory.

-

Communicate more actively through prominent disclosure of calories on menus and vending machines and front-of-package labeling systems to encourage healthier food choices.

None of these would be easy to adopt or implement, and as a country, I don’t believe that we are ready to embrace them. What is most important for now – and what Salt Sugar Fat might contribute to – is a change of attitudes toward these products. Smoking has declined in part because it has been stigmatized. We don’t need to stigmatize all processed foods and sodas, but we do need to associate public scorn with the 32-ounce soft drinks, oversized cookies, and the most egregious examples of salt, sugar, and fat poisoning our diet. Ideally, laws would not prohibit drug stores from giving away chocolate bars. Embarrassment would.