The Scorekeeper's Daughter

by james s. hirsch

This is one woman's story - about the loss of a father and the love of a son, about heartbreak and hope and community spirit, and about the circle of life, stretching from the ball fields of middle America to the battlefields of Iraq.

Ann Marie Kreft grew up in Cincinnati, the oldest daughter of a studious father whose great passions in life - sports and math - merged in his devotion to keeping baseball scores. John Kreft was once an official scorer for the Washington Senators. In the 1960s, while working as an accountant for the Cincinnati Reds, he took Ann Marie to games at Crosley Field, where they sat with their scorebooks on their laps and a radio at their side. At their home, John sometimes followed two baseball games simultaneously, one on television and one on radio, keeping scores of both. He used a sharp pencil to meticulously document each player's performance - hits and runs, put outs and assists - and even recorded the attendance, the names of the umpires, and the call letters of the radio station broadcasting the game.

John Kreft didn't talk about it much, but he had type 1 diabetes, diagnosed at age 12. In some regards, he was as vigilant about his diabetes as he was about his scorekeeping. Each morning, he tested his urine for sugar with Clinitest tablets, and his two daughters would gather around the test tube, which would heat up as the solution fizzed, bubbled, and changed colors. Blue meant there was no sugar in the urine. "Blue was a rare sight, so that was pure excitement," Ann Marie recalled. "It was almost always a shade of orange."

Her father stayed on a strict diet but only took one insulin injection each morning - a wholly inadequate regimen, we now know, but not unusual in those days. Ann Marie occasionally glimpsed his struggles. Once, when she went to her father's office, his boss showed her his wallet creased with teeth marks, where John had bit during a hypoglycemic seizure. Another time, during a baseball game, she saw her father slumped at a concession stand, trying to revive himself from a low.

But what Ann Marie most remembers are the complications. He developed retinopathy and, by 1972, tried to save his eyesight with laser therapy, which was still quite new. He continued to drive when he shouldn't have - his daughters had to tell him when the stop light had changed. He continued to keep baseball scores, but the markings now appeared more tentative and lighter, and fewer details were recorded. After leaving the Reds, he had a new employer but feared losing his job. The doctor visits mounted. His kidneys began to fail. He set up a special enhanced-vision monitor so he could work at home. It didn't help. He was fired, his wife later discovered, one day before his pension vested.

Ann Marie was not concerned that she would develop diabetes. She had heard that the disease "skipped a generation," leading her to believe that her children would be at risk. So she made a pact with a girl friend that the friend would bear her children. This was not idle girl talk. "It meant a lot to me," Ann Marie recalled, "because we were serious. I was not going to pass on diabetes to another child."

Her father's condition deteriorated. He used a kidney dialysis machine for almost a year when a new kidney was found for transplantation. The surgery took place in 1980, but the anti-rejection drugs were primitive. His body never accepted the new kidney, and John Kreft was never released from the hospital. He died at age 46.

Ann Marie, a 17-year-old senior in high school, would never forget the date of his death: December 5.

* * *

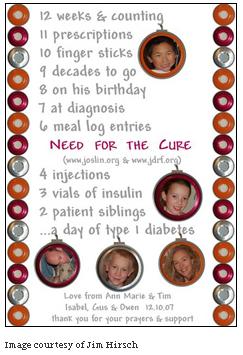

Diabetes was far removed from Ann Marie's world, though a year ago, Isabel befriended a girl who has type 1 diabetes. Her older sister has it as well. Ann Marie, watching the youngster test her blood sugar, saw how far things had come. She searched the Internet for more information, reacquainting herself with the symptoms of an undiagnosed patient.

Last September, on a Saturday, Ann Marie was running errands with Gus. Every place they stopped, the 7-year-old needed the bathroom. He had also been wetting his bed. The following morning, he ate breakfast, then ate a second breakfast, then ate a third but was still hungry. Ann Marie sent him to his room so she could get some work done. Then the terrible dawning arrived. She looked at her husband. "Gus has diabetes," she said. She didn't say anything else all day. She wanted a fasting blood sugar the following morning, so the family carried on its usual routine. She wanted Gus to have one more night of sleep, innocent of the coming storm.

At 6:30 a.m. the following morning, she called Rikki Conley, the mother of the diabetic girls, and she drove cross-town with a glucose meter. When Gus came down for breakfast, Rikki tested his blood sugar. Ann Marie knew she was looking for 125 or lower. The number flashed, and Rikki's lips turned down. The meter read 292.

"We went into the dining room," Ann Marie said, "and cried."

She told Gus that he would need to go to the doctor. Tim, who had a dentist check up that day, didn't fully appreciate what it all meant. "Should I skip my appointment?" he asked.

* * *

At Children's Hospital Boston, Ann Marie was thrust into a world that she had thought she left behind 27 years ago. "The desperate feelings became raw again," she said. She had little patience for the cheerful doctors and nurses who kept assuring her that her son would live a long, productive life. How long, and at what expense, with how much suffering, she thought. She was certain they'd all go home that night, to a warm bed and without a worry. Ann Marie was plenty worried. The doctors told her that she and Tim would now be Gus's pancreas, though she would later describe herself as more of a "sugar wrestler" than a body organ. After two days at the hospital, they had mastered the mechanics of injections and blood testing, and the doctors wanted to send them home. Tim was ready, but Ann Marie wasn't. "Why?" he asked.

"I don't want to ever go home again."

* * *

What kept her going was the love and support of her family and friends, who provided gifts, cards, and plenty of meals during those first weeks back home. Gus has an outstanding doctor and nurse at the Joslin Pediatric Clinic, and he made the initial adjustment as well as could be expected. Shortly after the diagnosis, Ann Marie faced the crucible of Halloween. Her three children were already assembling their costumes - Gus was "something ghoulish" - and devising special routes to maximize their haul. "I was wishing [Halloween] would just go away, but the closer we got, the more the fervor just mounted," Ann Marie said. "I imagined Gus with bags of candy for the next two months."

But then she had an idea. She had received an e-mail from a friend whose husband, Nathan Pincombe, a First Lieutenant. in the U.S. Air Force, had recently been deployed to Iraq, and the separation was difficult for all concerned. So why not send him a care package with the children's candy? In fact, why not ask Rikki if her family would like to participate as well?

"I thought it would be fun as a team effort," Ann Marie said. Besides, Gus had met Lt. Pincombe before and thought that he was one of those "extremist cool guys."

"He climbs rocks," Ann Marie said, "that no one should ever climb."

By Halloween, each school had placed an 80-gallon bin on its premises. Ann Marie doubted the barrels would be filled even half way. By the time she dropped off her kids the day after Halloween, the buses had already arrived - and the barrel had overflowed with sweets. "I thought we were going to be the only ones," Gus told his mom.

"You thought wrong," she said.

The three bins were removed a week later, each having been filled three times, with some items coming from miles outside of Weston. Rikki's three-car garage soon housed a collection of treats that would have made Willy Wonka proud. But how do you move thousands of pieces of candy more than 5,000 miles? The Iraqi heat could melt the chocolate, so the two families began separating the chocolate pieces into gallon-sized Ziploc bags. "I thought if I were in Iraq, I would rather have melted and reconstituted chocolate than none at all," Ann Marie reasoned.

To transport the goods, she asked nearby Hanscom Air Force Base about using a cargo plane and also asked the town's postal clerk if any programs existed to defray the costs. There was no help on those fronts, but assistance came from many quarters. In addition to the school principals, teachers, and school nurses, the project was supported by postal workers who would later help with the mailing, a custodian who helped haul the candy to Rikki's garage, local pastors and a community newspaper that spread the word, and friends and neighbors who helped pack up the boxes.

They filled 90 priority mailboxes in all - more than 1,000 pounds of candy! - each package requiring its own customs form. Also packed into each box was a postcard that featured Ann Marie and a group of children, with the e-mail addresses of the three school principals and the message: "Thank You percent Happy Holidays (And remember to brush!)."

Many of the boxes went to Lt. Pincombe, but they also went to other servicemen and women in Iraq and Afghanistan. Shipping cost about $800, paid for by Ann Marie and Rikki. It was the ultimate Candygram of good will, community spirit, and - to one woman in particular - solace.

* * *

The school principals forwarded the e-mails to Ann Marie as soon as they came in, and five arrived on the first day that the packages reached Baghdad. The timing was perfect. "It's just now the season where chocolate can arrive without melting, and we are grateful beyond comprehension," wrote Cpt. Marissa P. Mitchell. Other messages conveyed gratitude and grace. "I am new to Iraq," wrote Col. Mark Morrison. "I arrived only two months ago so I have a little under 10 months remaining. You were the first group to send me a care package, so it meant a lot."

The most poignant e-mail came from Lt. Pincombe himself, who gave everyone in his unit a package but still had boxes left over. So he took the remainder to a hospital near his base, where wounded American soldiers were awaiting planes to Europe or the U.S.

But, he wrote, "the primary tenants at this hospital are Iraqi soldiers, citizens, men, woman and a lot of children that have been injured. I will let you know how this turns out."

As Ann Marie read through those first-day e-mails, she suddenly realized something both haunting and beautiful, something that connected her to her past, something that suggested the entire effort was guided by a loving spirit. The e-mails had arrived on a day that she would never forget. It was December 5.

A new game had begun, and it won't end until the tiniest triumphs have been recorded, the greatest victories inscribed, and the last dream fulfilled.