A Technology Laggard’s Foray into Insulin Pumps and Continuous Sensors

by james s. hirsch

It’s fair to say that I’m a “technology laggard” and that even on my best days I have a love-hate relationship with gadgets. I’m not even on speaking terms with my cell phone.

But two years ago, I began using an insulin pump, primarily because I had a bad low and figured I needed to so something different. I went on the Animas. Then earlier this year, Roche wanted feedback on its new Accu-Chek pump, so I tried that for four months.

When that trial was over, I took another detour and bought the OmniPod, which unexpectantly led me DexCom’s continuous glucose monitor. I had resisted CGM for the same reason I’ve resisted having a Blackberry: I avoid most new technologies. But OmniPod’s manufacturer, Insulet, for various reasons wanted me to use its insulin pump in conjunction with CGM, so it paid for three months of supplies. I got another break when DexCom kindly upgraded me to its seven-day sensor, even before it was available to the public.

So for one who barely knows how to use the television remote, I was now wearing the latest, most sophisticated diabetes technology in the world. Have I found glycemic paradise? I wouldn’t go that far. But after three weeks, I can say that the OmniPod – at least for me – is an incremental but clear improvement over traditional pumps, while CGM has the potential to transform care. I also believe the real power in these devices is less physiological than psychological, tools that can shape and manipulate behavior in unexpected ways. I compare my CGM to a benevolent mother-in-law whose intrusions can be overbearing but who ultimately has your best interest at heart.

The OmniPod is different. As my colleague Kelly Close described in our last diaTribe issue, the pod is the first “tubeless” pump. Attached to the body, it delivers insulin via signals from a wireless hand-held Personal Diabetes Manager (PDM), and the pods are replaced every three days. The infusion process is automated, quick, and easy. No priming. No air bubbles. No piston rods. The automated insertion is less painful than a fingerprick, and I’ve had no occlusions.

.JPG)

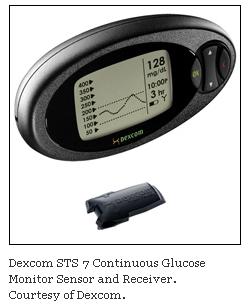

A friend of mine with diabetes once said to me: “I just don’t know how I feel.” Well, real-time CGM finally tells us how we feel, at least in terms of blood sugar. The DexCom comes with an “applicator,” which injects or inserts the “sensor probe” beneath the skin. Attached on top of the skin is the transmitter, which signals a glucose reading every five minutes to a receiver, and the receiver displays your most recent reading plus trend lines over the past one, three, and nine hours.

My first few days on the DexCom STS – the company’s first generation product – were disappointing, because I had so many “data gaps” and “noise.” The first night, the alarms woke me up just to tell me the receiver wasn’t receiving any information. Couldn’t that news wait until morning?

I’ve had better success with the SEVEN, the company’s next generation sensor that can stay in your body for seven days. The most obvious difference is just that – longer duration, fewer insertions of new sensors. But the insertion itself is less painful, as a smaller needle is used. I’ve also learned to be more forgiving. It appears to take the sensor about 24 hours to get used to its new surroundings, so that first day will have some data gaps and inaccurate readings; but then it becomes more consistent. The receiver also requires daily maintenance: it must be charged once a day like a cell phone, and it must be calibrated every 12 hours by doing a fingerstick with a OneTouch meter and then “uploading” the meter onto the receiver with a cable.

The DexCom is not approved to replace fingersticks, and it’s true that at times there have been 40 or 50 point differences between my DexCom receiver and my meter reading. So I don’t entirely trust the DexCom, but the longer I’m with it, the more faith I have. It’s already “caught” three or four mild nighttime lows – that is, it began vibrating while I was still sleeping. (I believe I’ve had these lows because with the OmniPod, I’m no longer losing insulin from air bubbles in the tube.) It helps to have a tolerant partner with you in bed. One night, when my DexCom alarm buzzed and sent a frisson of electricity across the mattress, my wife lifted her head and said, “You’re vibrating.”

Of such pillow talk are great marriages made.

The glucose readings provide fresh insights into familiar actions. I’ve always known how easy it is to overtreat a low, but I really understood it when I drank a modest glass of orange juice and saw the glucose trend line spike from 60 to 183. The sharp decline while exercising is equally fascinating.

There is something futuristic about the entire enterprise. I see the trend line falling rapidly. I don’t feel anything yet, but I know I have to act. I eat a snack and patiently watch the receiver. Finally, I see the trend line straighten out, and I want to announce, Glucose stabilized . . . Beam me up, Scotty!

On another occasion, my blood sugar started to fall when I was stuck in a traffic jam – about the worse time possible, of course, to become hypoglycemic. So I started eating some Skittles and watching the receiver . . . eating and watching . . . watching and eating . . . until it finally felt as though I were treating the receiver and not my blood sugar. And who can blame me? If I went low, my DexCom would buzz, alarm, reprimand, scold, hold me accountable, and all but lecture me on my failure to take proper precaution. Not the most pleasant riding mate, but it beats passing out at the wheel.

I will remain skeptical about new technology, and I know that these gadgets in particular don’t always work, they’re cumbersome, and they’re expensive; but their ability to change behavior is their underlying power. For either CGM or insulin pumps to work, patients must be highly motivated – uploading, calculating, calibrating, counting, trouble shooting, and observing. Always observing. That will exclude some, and perhaps many, diabetics who don’t have the time, interest, or resources to invest in their health.

But if you believe that diabetes is an endless dance to the same old song, we now have some new partners who can engage, enrapture, and even awe us, long into the night.