Using the GMI to Estimate Your A1C: How Accurate Is It?

By Dr. Diana Isaacs

By Dr. Diana Isaacs

GMI provides an estimated A1C level based on continuous glucose monitoring data and can avoid some of the limitations of A1C tests. A recent study compared actual A1C levels with GMI to see how the two compared in the real world.

The A1C test is commonly used to assess a person’s glucose management. A higher A1C is associated with higher glucose levels and more health complications. Although long considered a gold standard in diabetes care, the A1C has a huge limitation: it’s just an average. A person could spend a lot of time with low blood sugar levels and a lot of time with high blood sugar levels, yet have an A1C under 7%, which is the target for most people with diabetes. You can learn more about the limitations of A1C here.

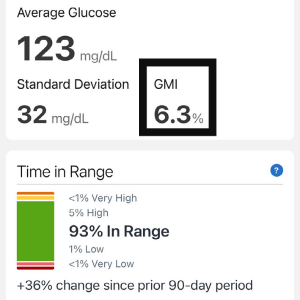

For those who wear a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGM), the glucose management indicator (GMI) essentially estimates A1C – in fact, it used to be called an “estimated A1C.” Without the need for a blood draw, it takes the average of your glucose readings and uses a formula to estimate what your A1C is expected to be. To calculate GMI you should have at least 14 days of data.

Your glucose management can also be measured by Time in Range (TIR, when glucose levels are between 70 to 180mg/dL), Time Below Range (glucose levels below 70mg/dL) and Time Above Range (glucose levels over 180mg/dL). Generally, a Time in Range of 70% or greater is equivalent to an A1C of 7% or less. This data is quite useful to see if you are meeting your glucose targets or if you need to adjust your diabetes treatment plan. Learn about TIR and how it can help your diabetes management here.

Differences between GMI and A1C

Differences between GMI and A1C

An A1C is based on red blood cell turnover and provides an average of blood glucose levels over two to three months, since that’s how long it takes for new red blood cells to form. For this reason, your A1C level is usually only obtained quarterly. A GMI, on the other hand, can be checked much more frequently since it is based on CGM data.

But how accurate is the GMI? Is it realistic to expect that your A1C will be exactly what the GMI shows on your CGM report? There are some important things to know about A1C:

-

Since it is based on red blood cell turnover, anything that affects red blood cells could falsely skew your A1C number. This includes anemia and genetic conditions that affect hemoglobin, such as sickle cell disease.

-

Many people with chronic kidney disease have falsely low A1C.

-

Studies show that people of color have slightly higher average A1C levels than white people. This includes Black, Asian, Hispanic and Indigenous individuals.

A Real-World Analysis

A recent study by the University of Washington looked at how GMI compares to actual A1C. Although GMI is one of the key CGM metrics and it’s used by healthcare professionals and people with diabetes when analyzing glucose reports, little information exists in the real world setting on how it compares to A1C.

The investigators at the University of Washington Diabetes Care Center looked at data from 641 people with diabetes between 2012 to 2019. People had a documented A1C within 30 days before or after the healthcare visit when the CGM report was uploaded. The CGM report had to contain at least 14 days of data with at least 95% data sufficiency, meaning that at least 95% of glucose values were recorded during a 24-hour period. If a lot of CGM data were missing, due to being too far from the receiver or going too long without scanning the sensor, the GMI could be less accurate.

In the study group:

-

The average age was 46 years

-

52% of people were female

-

Most were Caucasian (93%)

-

Most had type 1 diabetes (91%)

-

The most common CGM used was Dexcom G5, which requires two calibrations per day

-

The Dexcom G6, Freestyle Libre, Medtronic Enlite, and Medtronic Guardian were also used

-

The average period for a CGM report was 24.5 days (the range was 14-144 days)

-

The average A1C was 7.3%

-

The average of mean CGM glucose was 162 mg/dL (the range was 85-296 mg/dL)

The Findings

In comparing A1C levels to GMI, the study found:

-

Only 11% of people showed less than a 0.1 percentage point difference between their A1C and GMI. This means if their GMI was 7.0%, their A1C was between 6.9-7.1%.

-

50% of people had differences of 0.5 percentage points or less. This means if GMI was 7%, actual A1C ranged from 6.5%-7.5%.

-

22% of people had a difference of 1 percentage point or greater, meaning if GMI was 7%, actual A1C was under 6% or over 8%.

The researchers were surprised at these discrepancies, since they are greater than what was observed in previous trials, and the researchers looked to see what may have contributed to the large differences between A1C and GMI. They found that people with type 1 diabetes had 0.17 percentage points less of a difference between GMI and A1C compared to those with type 2 diabetes, although this was not statistically significant (it’s possible this was just a chance finding). People that had reduced kidney function had a 0.19 percentage point greater A1C and GMI difference. This was less surprising since kidney disease can falsely lower A1C values, causing a greater discrepancy. They did not find differences based on CGM device.

Limitations of this Study

This is just one study, and it was retrospective, meaning that researchers looked back in their data base, and outside factors were not controlled. For example, if a medication change was made at the visit, and the A1C was drawn a month later, that would have caused the results to be different from the CGM report. A perfect comparison would require a GMI and A1C taken on the same day with 60-90 days of CGM data. Additionally, a wide variety of CGM devices were used, and some of the older CGM devices were less accurate than the ones we typically use today. Many of the devices required calibration, which can also introduce biases with accuracy depending on the quality of the calibrations. Finally, the study population was mostly Caucasian and lacked diversity.

Application to the Real World

The GMI provides a clue as to what your next A1C result might be, but don’t be surprised if they aren’t a perfect match. The good news is that most people had results within 0.5 percentage points, meaning the two values should still be somewhat close. The GMI may actually be more reflective of true average glucose since there is not any lab interference. Many healthcare offices have been relying on GMI more during COVID-19 when it’s been challenging to get the lab test.

While A1C and GMI provide a measure of how your glucose management is working, keep in mind that both are just averages. Try focusing on your Time in Range, a metric you can compare day-to-day and week-to-week. If you can increase your TIR, especially focusing on a TIR of 70% or greater, your GMI and A1C are much more likely to also reach their targets. However, if you don’t reach your A1C and GMI goals, please don’t be disappointed. It’s possible to lower A1C and GMI by having tons of hypoglycemia, but this is not good for short-term or long-term health outcomes. If you focus on that Time in Range, you are more likely to feel good and have great diabetes outcomes.

This article is part of a series on Time in Range.

The diaTribe Foundation, in concert with the Time in Range Coalition, is committed to helping people with diabetes and their caregivers understand Time in Range to maximize patients' health. Learn more about the Time in Range Coalition here.

About Diana

Diana Isaacs, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, BC-ADM, CDCES is a clinical pharmacist and diabetes care and education specialist at the Cleveland Clinic Diabetes Center where she coordinates the CGM and remote monitoring programs. She was the 2020 ADCES Diabetes Care and Education Specialist of the Year and serves on the ADA Professional Practice Committee, the committee that updates the ADA Standards of Care. She is passionate about helping people with diabetes and has had the honor to start thousands of people with diabetes on CGM.