What's a 'Normal' A1C? When is it Misleading?

By Adithi Gandhi and Jeemin Kwon

By Adithi Gandhi and Jeemin Kwon

Why we use A1C, what values are recommended, and what impacts A1C – everything from anemia to vitamins

Hemoglobin A1C (“HbA1c” or just “A1c”) is the standard for measuring blood sugar management in people with diabetes. A1C reflects average blood sugars over 2 to 3 months, and through studies like DCCT and UKPDS, higher A1C levels have been shown to be associated with the risk of diabetes complications (kidney and nerve disease). For every 1% decrease in A1C, there is significant protection against those complications.

However, as an average over a period of months, A1C cannot capture critical information such as time spent in a target range (70-180 mg/dl) and below range (less than 70 mg/dl).

This article describes why A1C is used in the first place, as well as factors that can lead to misleadingly high or low values. In a follow-up piece, we will discuss time-in-range, blood sugar variability, and how to measure and interpret them.

What is A1C and why is it used?

A1C estimates a person’s average blood sugar levels over a 2 to 3-month span. It is one measure we have of how well blood glucose is controlled and an indicator of diabetes management.

Though A1C doesn’t provide day-to-day information, lower A1Cs are correlated with a lower risk of “microvascular” complications, such as kidney disease (nephropathy), vision loss (retinopathy), and nerve damage (neuropathy). Similarly, higher A1Cs can lead to "macrovascular" complications, such as heart disease.

A1C is usually measured in a lab with routine blood work, or with a countertop machine in a doctor’s office (and some pharmacies) using a fingerstick.

A1C measures the relative percentage of “glycated hemoglobin,” which refers to red blood cells called hemoglobin with sugar attached to it. If a person consistently has higher blood glucose levels, A1C levels go up because more red blood cells are coated with sugar. The test is representative of a 2 to 3-month average because once a red blood cell becomes coated with sugar, the link is irreversible. It is only when the red blood cell is "recycled" (which happens every 2 to 3 months) that the sugar coating disappears.

What are “normal” A1C levels for people who don't have diabetes?

Generally, high A1C values indicate high average blood sugar levels and that a person might be at risk for or may have diabetes. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has established the following cutoffs:

A1C Chart

| A1C Level | What It Means |

|---|---|

| A1C < 5.7% | Normal (minimal Risk for Type 2 Diabetes) Your average blood glucose level for the last 2-3 months is in the same range as someone who doesn’t have diabetes. |

| A1C Between 5.7% to 6.4% |

“Prediabetes”, meaning at risk for developing type 2 diabetes Your average blood glucose level is higher than normal, but not high enough to be considered type 2 diabetes. |

| A1C > 6.5% | Diagnosed diabetes Your average blood glucose level for the last 2-3 months is at the level of someone with type 2 diabetes. |

Make sure you get a regular A1C test, especially if you think you might be at risk for diabetes.

What is an A1C goal for those with diagnosed diabetes?

An A1C of less than 6.5% or 7% is the goal for many people with diabetes. Since each person with diabetes is unique, however, healthcare providers are recommended to set individual A1C goals. For instance, goals may differ depending on age and other health conditions.

How does age affect A1C?

A1C is a measure of diabetes management, so your A1C won't naturally shift as you get older. However, as you age your diabetes management strategies and A1C goals may change – for example, younger people may be more focused on reducing long-term health complications, while older people may concentrate on avoiding severe lows. Talk with your healthcare professional if you're curious about how your age may affect your A1C levels.

Where is A1C misleading or potentially inaccurate?

Much progress has been made in standardizing and improving the accuracy of the A1C test thanks to the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP). Results from a non-NGSP certified lab may not be as reliable. Depending on the machine, a single A1C test can have up to a 0.5% margin of error, which means the “true” value might be 0.5% higher or lower than the measured A1C. For example, if a lab report shows an A1C value of 7.0%, the actual A1C value might range from 6.5% and 7.5%.

A1C is based on a person’s red blood cell turnover (the lifespan of a red blood cell) and the quantity of sugar attached to each cell. Certain conditions, such as kidney disease, hemoglobin variants, certain types of anemia, and certain drugs and vitamins, impact red blood cell turnover, leading to misleading A1C values. Click here to jump down to a list of factors that impact A1C.

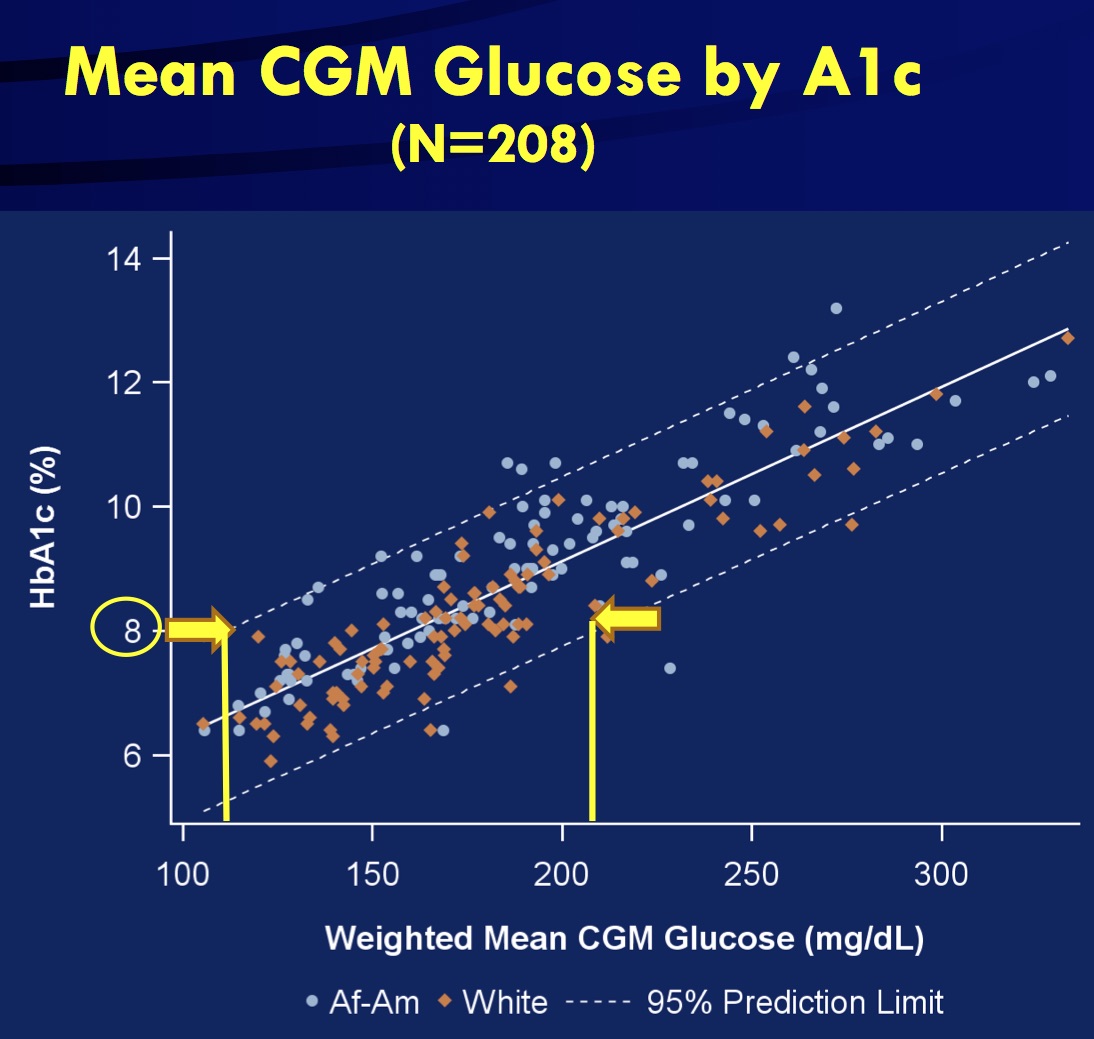

The relationship between A1C values and average blood sugar levels can also vary markedly from person to person. In studies using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), 24/7 blood sugar levels can be compared to a measured A1C. These studies reveal considerable variation from person to person. For instance, an 8% A1C value in one person could reflect an average blood sugar of 140 mg/dl, while in another it could be 220 mg/dl. This variation relates to individual differences in how red blood cells and blood sugars bind the lifespan of red blood cells.

"An A1C of 8% can correspond to an average blood sugar of 140 mg/dl in one person, while in another it could be 220 mg/dl."

A1C to Blood Sugar Conversion

| A1C = 5 | 80 mg/dl | 4.7 mmol/L |

| A1C = 6 | 115 mg/dl | 6.3 mmol/L |

| A1C = 7 | 150 mg/dl | 8.2 mmol/L |

| A1C = 8 | 180 mg/dl | 10 mmol/L |

| A1C = 9 | 215 mg/dl | 11.9 mmol/L |

| A1C = 10 | 250 mg/dl | 13.7 mmol/L |

| A1C = 11 | 280 mg/dl | 15.6 mmol/L |

| A1C = 12 | 315 mg/dl | 17.4 mmol/L |

| A1C = 13 | 350 mg/dl | 19.3 mmol/L |

| A1C = 14 | 380 mg/dl | 21.1 mmol/L |

For looking at an individual’s glucose values, CGM is a better tool for measuring average sugar levels, time-in-range, and time below range. Learn more in our previous beyond A1C article here.

What tools are available if an A1C test is not accurate or sufficient?

Besides A1C tests, the most common measures of blood sugar are the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), CGM, and self-monitored blood glucose tests.

The OGTT is a diagnostic tool diabetes and prediabetes, assessing a person’s response to consuming a fixed amount of sugar. After taking the sugar drink, blood sugar levels are measured two hours later. Below 140 mg/dl is considered “normal,” between 140 mg/dl and 200 mg/dl points to prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, and above 200 mg/dl indicates diabetes. It is not useful for tracking diabetes management.

For those with established diabetes, CGM has the advantage of monitoring blood sugar levels consistently throughout the day (every 5-15 minutes), providing more detailed insight into time in range, low blood sugars, and high blood sugars.

If CGM is not available, taking frequent fingersticks with a blood glucose meter – when waking up, before and after meals, and before bed – can also indicate when blood sugar levels are going low, high, and staying in range.

What’s important to keep in mind about A1C?

If you have diabetes, it’s also important to take the perspective that A1C is not a “grade” on diabetes management, but rather a helpful measurement tool that you and your healthcare providers can use to guide decisions and assess the risk of complications.

Non-glycemic factors that can affect A1C:

While there are many unsuspecting factors that can impact A1C, the information in the table below is not meant to invalidate the A1C test. Rather, knowing how certain conditions and factors can change A1C levels is a key part of using A1C as one measure of diabetes management.

Many of the conditions that affect A1C results are related to changes in the turnover of red blood cells, and thus notably, types of anemia. Correction of anemia by treatment can also affect A1C results.

Untreated anemia

Untreated anemia can be caused by iron deficiency or vitamin B-12 deficiency. Untreated anemia can misleadingly increase A1C values due to decreased production of red blood cells. To test for anemia, ask your healthcare provider about taking a complete blood count (CBC) test.

Asplenia (decreased spleen function)

The spleen is involved in the production and removal of red blood cells. Decreased spleen function, may be caused by surgical removal, congenital disorders, or other blood disorders such as sickle cell disease. This may lead to misleadingly increased A1C. Asplenia can be identified by MRI, echocardiogram, chest X-ray, or a screening test.

Blood loss and blood transfusions

The body’s response to recent blood loss (create more blood cells) or blood transfusion can misleadingly lower A1C, but the next A1C test should return to a more representative reading. Let your healthcare provider know if you have recently received a blood transfusion.

Cirrhosis of the liver

Cirrhosis refers to chronic liver damage that leads to scarring. Cirrhosis, in addition to affecting response to glucose-lowering medications – including insulin – may misleadingly lower A1C values. Ask your healthcare provider about a liver examination.

Hemoglobinopathy and Thalassemia

Hemoglobinopathy results in abnormal hemoglobin and thalassemia refers to the lower production of functional hemoglobin. Depending on the abnormal form of hemoglobin, hemoglobinopathy can result in either increased or decreased A1C values. Thalassemia can misleadingly lower A1C values due to early destruction of red blood cells. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any known family members that have had thalassemia.

Hemolysis (rapid destruction of red blood cells)

Hemolysis may misleadingly lower A1C values due to the shortened red blood cell lifespan. This condition may be caused by an inappropriate immune response and artificial heart valves.

Untreated hypothyroidism (low levels of thyroid hormone)

Hypothyroidism may misleadingly increase A1C, while treatment with thyroid hormone can lower A1C. Ask your healthcare provider about taking blood tests that measure thyroid function.

Pregnancy

Decreased red blood cell lifespan and increase in red blood cell production may misleadingly lower A1C values in both early and late pregnancy. Ask about taking an oral glucose tolerance test, which is used to diagnose gestational diabetes. A common practice for pregnant people with diabetes is to use CGM.

Uremia (high levels of waste (normally filtered by kidneys) in the blood)

Untreated uremia may misleadingly increase A1C values. Dialysis is used to treat uremia – in this case, A1C is not a suitable test.

Medications

Medications that may misleadingly increase A1C include:

-

Opioids (pain relievers): Duragesic (fentanyl), Norco/Vicodin (hydrocodone), Dilaudid (hydromorphone), Astramorph/Avinza (morphine), or OxyContin/Percocet (oxycodone)

-

Long-term use of over 500 mg of aspirin a day or more

Medications that may misleadingly lower A1C include:

-

Erythropoietin (EPO)

-

Azcone (dapsone)

-

Virazole/Rebetol/Copegus (ribavirin)

-

HIV medications (NRTIs): Emtriva, Epivir, Retrovir, Videx-EC, Viread, Zerit, or Ziagen

Always discuss the appropriate use of opioids for pain and their possible effect on A1C as well. Tell your healthcare provider if you are taking any of these medications prior to your A1C test.